Excess Returns

I have learned my lesson. Last Tuesday’s column described a research method called “factor analysis,” then discussed its findings. A poor decision. My article was neither fish nor fowl. To mix the metaphor, it was a platypus. After squandering half of my virtual ink on the windup, I ended up shortchanging the main topic: how factor analysis supports Jack Bogle’s key investment precepts.

I will make no such blunder today. If you wish to understand in some detail how factor analysis works, here are three links. (Beware: They are not quick reads.) Otherwise, I will immediately cut to the chase: using factor analysis to identify U.S. stock funds that have notched persistently high excess returns.

Rather than compare a fund’s performance against either a peer group or common index, factor analysis creates a customized benchmark. Each fund is compared against an individualized model. This article addresses the “excess returns” that appear after applying that model—that is, the portion of fund performance that the factor-analysis technique cannot explain.

(A brief example: The model calculates that over a 10-year period, a fund using that particular investment strategy should have returned 8.5% per year. In fact, the fund gained an annualized 8.2%. Its excess returns are therefore negative 0.3%.)

This column will address three questions. One, how many funds posted high excess returns over two consecutive periods? Second, should we credit their portfolio managers for such success, or do those figures merely reflect the limitations of the factor-analysis model? Third, what are those winning funds?

Issue #1: How Many Funds?

I conducted the study screening for the oldest share class of all diversified U.S. equity funds, both open-end and exchange-traded, that existed from April 2013 through March 2023. For each half of the period, I calculated the funds’ excess returns (using a three-factor model) during that decade. I defined persistent funds as those with excess returns that ranked in the top decile on both occasions.

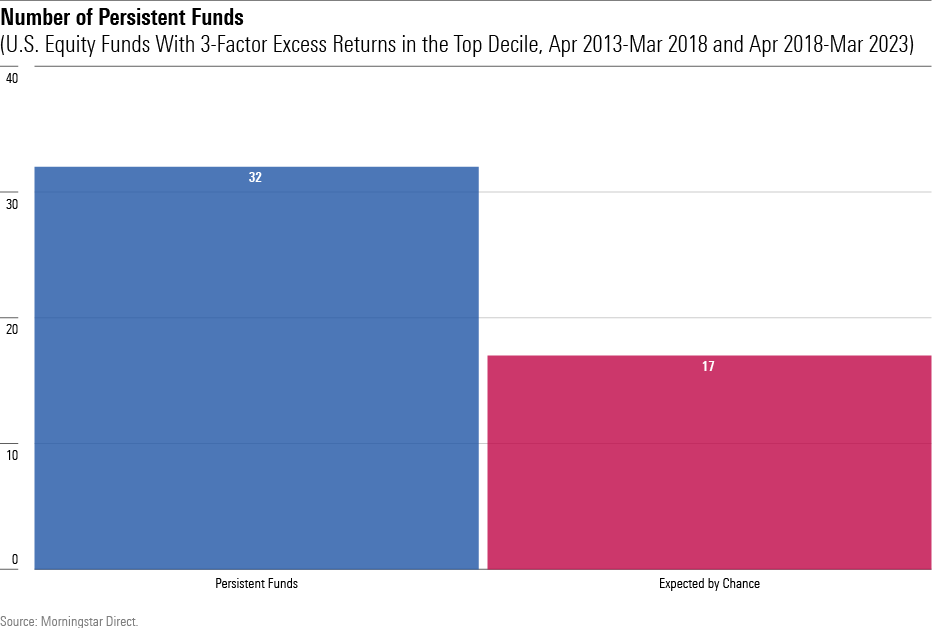

The study contained 1,655 funds. If the results were random, one fund in 100 would land in the top decile both times, making for median expectation of 17 funds. In fact, 32 funds hit the mark. It seems that true persistence does exist.

(Time for a quick brain teaser. What is the likelihood that those 32 funds passed the screens solely by chance? That is, if a 100-sided die were rolled 1,655 times, what is the probability that it would land on “7″ at least 32 times? My intuition told me that figure was quite small, say 1%. I greatly overstated the matter. The actual answer is 0.05%—once in every 2,000 simulations. A rare event indeed.)

Issue #2: Interpretation

Now comes the tricky part. That the findings are statistically significant is good news for those seeking persistently successful funds. However, as previously mentioned, that development could owe to the model’s imperfection. If the factor analysis houses a blind spot, those “excess returns” might be only sound and fury, signifying nothing about the abilities of the funds’ portfolio managers.

That concern is valid. As abnormally skilled managers presumably are scattered across the fund universe, rather than assigned only to funds that follow certain strategies, one would expect the winners’ list to be spread among the various fund categories. But that is not the case. Of the 32 funds with persistently high excess returns, a whopping 30 invest in some form of growth stocks.